You never miss a work deadline, you don’t break rules, you never want to let anyone down. That’s what good people do, right?

Maybe you end up doing whatever everyone else wants. If everyone else is happy, then there is peace, and life is so much simpler. Letting someone down when they’re counting on you surely makes you a bad person.

Then you burn out at work – your job is important to you, and people are relying on you and you cannot take time off even if your body is screaming with tiredness. Maybe you let your partner have sex with you even when you didn’t really want to have sex – they have a high sex drive and you weren’t in the mood, but if you deny them sex then surely you’re mean one?

If any of this sounds familiar then keep reading because this article is for you. This is more of an essay than an article, but stick with it.

Saying no is one of the most important factors to our wellbeing. Saying no keeps us safe from those who want to take more from us than we can give. The ability to say no means that we are in touch with ourselves and how we really feel.

Importantly, if we can’t say the word no, then our mind and bodies will end up saying no for us.

Here’s a brief overview of a psychoanalytic view into how we lose the capacity to say no, and why this is a bad thing.

Sigmund Freud – our minds have incorporated parental, societal and cultural views

Psychoanalytic theory has a rich history of exploring our lives from cradle to the grave, with one of its most essential premises being that our earliest experiences really matter. They shape us, and that these early experiences continue to affect us throughout our lives.

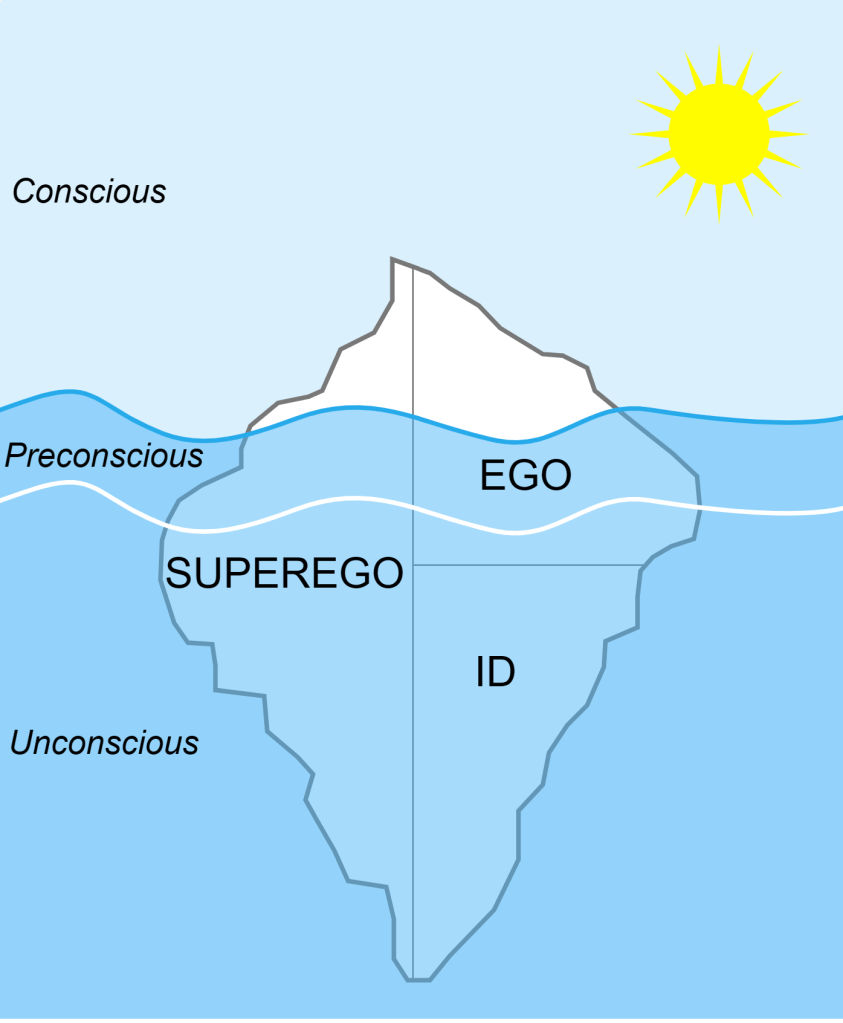

Sigmund Freud theorised that childhood is the crucible within which our minds develop, and he formed his famous model of mind that included the ego (the I), the Id (the It) and the super-ego (the above-I). Freud believed that most of the mind is actually unconscious, that is to say, that we are mostly unaware of our minds, which is why a lot of our own thoughts, wishes and behaviour can confuse us.

Image from Wikipedia

To Freud, the Id is the pleasure-seeking part of our mind that demands gratification and satisfaction of our desires. This part of the mind is completely unconscious. Unfortunately, what we might desire and might bring us pleasure, might not be compatible with what society and civilization expect from us, so there may be times where the ego represses what the Id is demanding. The ego only allows desires that it deems to be compatible with reality into consciousness (i.e. into our awareness).

The super-ego (also unconscious) is an interesting part of the mind, because this is the part of our minds that has really absorbed the messages society, family members, and the culture we grew up in – it is the part of our minds that tells us off for having thoughts that are not compatible with what society, culture and family might want or expect of us.

In other words, part of our own minds isn’t really our own because we have absorbed societal, cultural and parental norms.

A key tenet of Freudian psychoanalysis is that we are in conflict with ourselves. We have our own desires that we seek to bring us pleasure (the Id) but sometimes these desires might bring us into conflict with societal, cultural and parental norms, and we are tormented by never being able to get the thing that we actually want.

But what does this have to do with the capacity to say no? Our own minds (ego and super-ego) are saying no to us because it is not what society wants from us. The super-ego can often be quite harsh, and some people really struggle with the internal pressure of not being as “good” as our own minds (which includes the demands of society, culture and family) want us to be.

Donald Winnicott and the ‘False Self’

We all live in society and we are all aware of what society expects from us. But then how can we find out what really makes us happy, and live our lives so that we are not automatons blindly doing whatever everyone else wants from us. Excessive obedience and compliance can lead to things such as burn out and submitting to behaviours from others that we should not be expected to tolerate.

Donald Winnicott developed Freud’s ideas further, particularly Freud’s ideas about playing and creativity. Winnicott was a paediatrician who spent time with thousands of mothers and children and developed timeless theories about how parents can help their children come into “being”; in other words, how children can become their true selves and find out what brings them happiness and satisfaction, despite living within the restraints, rules and laws of society and culture.

Human babies are believed to be born too soon – upon birth, unlike other mammals and other members of the animal kingdom, human beings are entirely dependent on their caregivers – unable to lift their own heads, let alone stand up and walk. In this helpless state, the baby is completely reliant on others.

Our first relationship with another person that we become aware of in this helpless state is usually our mother.

Babies can barely open their eyes and cannot actually see anything, but realise that their circumstances have changed, and that they are no longer in the infinite bliss that is the womb. Winnicott believed that in order to have a healthy transition from being a neonate to around 3 months old, all the baby’s needs to be met in this crucial newborn period (giving the baby an illusion of omnipotence). Later the baby will need to become ‘disillusioned’ from its belief that it is omnipotent, but this comes later, and requires the mother to gradually and gently let her baby cope with every day frustrations.

As the baby opens its eyes and starts to see, one of the first things that the baby is fascinated by is seeing his or her mother. Mothers and babies often gaze at each other for a long while, and Winnicott believed that the baby’s first “mirror” was their experience of their mother’s face. To Winnicott, the baby wants the mother to reflect back to them what the baby is experiencing. Babies can sometimes be harsh to their mothers – and Winnicott felt that if the mother retaliated with rejection, then this is the beginning of compliance for the baby.

Image by Vânia Dos Santos from Pixabay

Compliance in of itself might not sound that bad, but Winnicott suggested that this is the beginning of the origin of the ‘False Self’ – this is the self that the baby/infant/child feels can be loved by others, because the way they really are (the ‘True Self’) is not acceptable to others, and they will not be loved if they do not conform.

In this False Self situation, as we get older we get more and more messages about what we have to do to be acceptable to others – to parents, to society, to culture – and we end us saying no to ourselves – we repress what we really want to do, and this can make us miserable. It can get to the point, when saying no to something that is actually causing us harm feels wrong.

Society sends women horribly complex messages when it comes to sex – women are to be both grateful to be considered to be desirable, but also not too sexual because then they are “sluts” – in this confusion and muddle, women often end up being confused about whether they can say no to sex, and whether they are consenting to sex or whether they have been coerced or raped.

In a racialised society, people of minority races are often told that they should say no to themselves – they should not demand equality, and doing so means they are being “difficult” or “playing the race card”.

And it’s not just women of all colours and racialised people; white men also struggle in society. Society, parents, culture tell us to work hard, and that letting people down is basically failing. People who work in “helping professions” really struggle with saying no to working beyond their means – medicine, teaching, police, and all professions where people feel their purpose is to help someone else, all struggle with saying no to unreasonable work cultures and demands, and this can easily lead to burn out.

When we can’t hear our minds saying no, our bodies say no for us

Going to back to Freud and psychoanalysis, Freud famously said that “the ego is first and foremost a bodily ego”. This means that psychoanalytic theory believes that the mind is in the body. Feelings can be expressed through the body. Imagine how your heart races when you’re excited, how your cheeks burn when you’re embarrassed, how you might get pain in your gut when you’re anxious – all these are physical manifestations of emotions.

And when we feel we can’t say no, despite what our emotions are telling us, then our bodies will say no for us. This can be something very obvious like being too tired to get out of bed. But it can also include illnesses. Physical illnesses can have clear causes (e.g. a bacterial infection is caused by bacteria, which means you need an antibiotic to clear the infection). However, there are some physical conditions that are linked to emotions. These include asthma, IBS, eczema, and most illnesses that have auto-immune involvement.

So when we feel we can’t say no, our bodies will tell us to stop. For example, asthma increases the risk of pneumonia. Severe pneumonia can be life-threatening, but even a mild case will necessitate time off work, which means you have to stop what you are doing. Your body has said no and you cannot carry on like you were.

Wouldn’t it be easier to listen to your mind before your body says no?

How can we learn to say no?

Let’s recap. We become socialised from a very young age to conform to parental, societal and cultural expectations. So much so that our own minds tell us off for wanting to do things that go against what the world demands from us.

In this case, how on earth can we learn to say no to the things we don’t want to do (without acting like sociopaths)?

Winnicott also provided some answers here. And his answer was a rather beautiful one.

We need to play.

“It is in playing and only in playing that the child or adult is able to be creative and use the whole personality, and it is only in being creative that the individual discovers the self.”

Donald Winnicott

Playing and creativity are voyages of discovery. It is when we are playing that we are being creative, and it is playing that we test the limits of our understanding of ourselves and the world. We find out what makes us scared, we realise what makes us laugh, we start to appreciate what we love in ourselves and others, we discover what we are good at, we gain an understanding of where we need help from others, we push the limits and learn more than we could ever know if we are simply told what to do and think.

It is in playing that we realise what we don’t want to do, and therefore what we want to say no to.

It’s not all on us though; we also need an environment and culture that allows us to say no. This can go back to what Winnicott said about our first mirror being our mother’s face and whether we feel rejected if we say no. It depends on our families, schools, societies and cultures to allow us to show that if we say no, we won’t be punished harshly and lose love.

Without this, we run the risk of being trampled over because we can’t say no.

Leave a comment